Frédéric Chopin: Nothing is more odious than music without hidden meaning

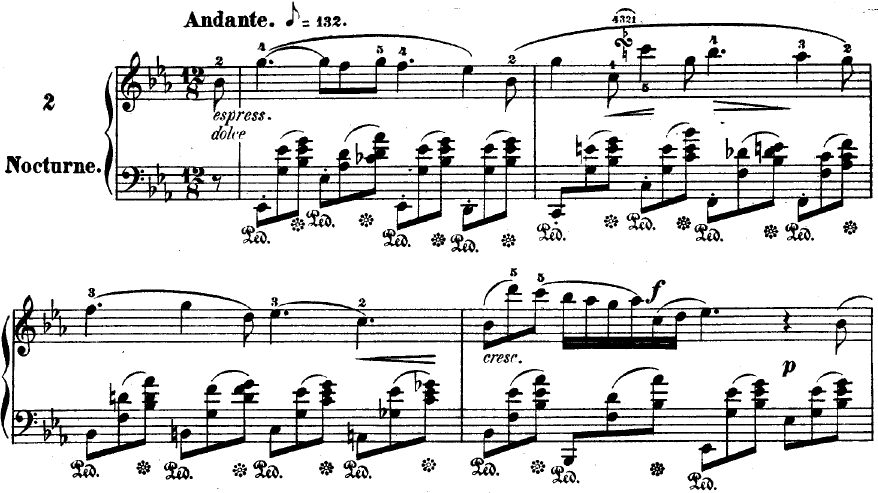

“Who does Chopin resemble? His own music.” With this seemingly simple and concise definition, composer and pianist Ignaz Moscheles, a nineteenth-century salon lion, concluded a perfect portrait of Frédéric Chopin, a composer with a complex character that was sometimes mysterious and elusive. In fact, he was above all a poet and only then a musician. I’ve always adored Chopin, and I still turn to him today when I treat myself to classical music. I love playing Chopin as well. I always feel that each Nocturne is a free interpretation of the emotions I’m filled with at that moment. I know that my beloved piano teacher Marija won’t agree with this, but I always felt Chopin in my own way, and I imagine that everyone who picks up his sheet music has the same feeling.

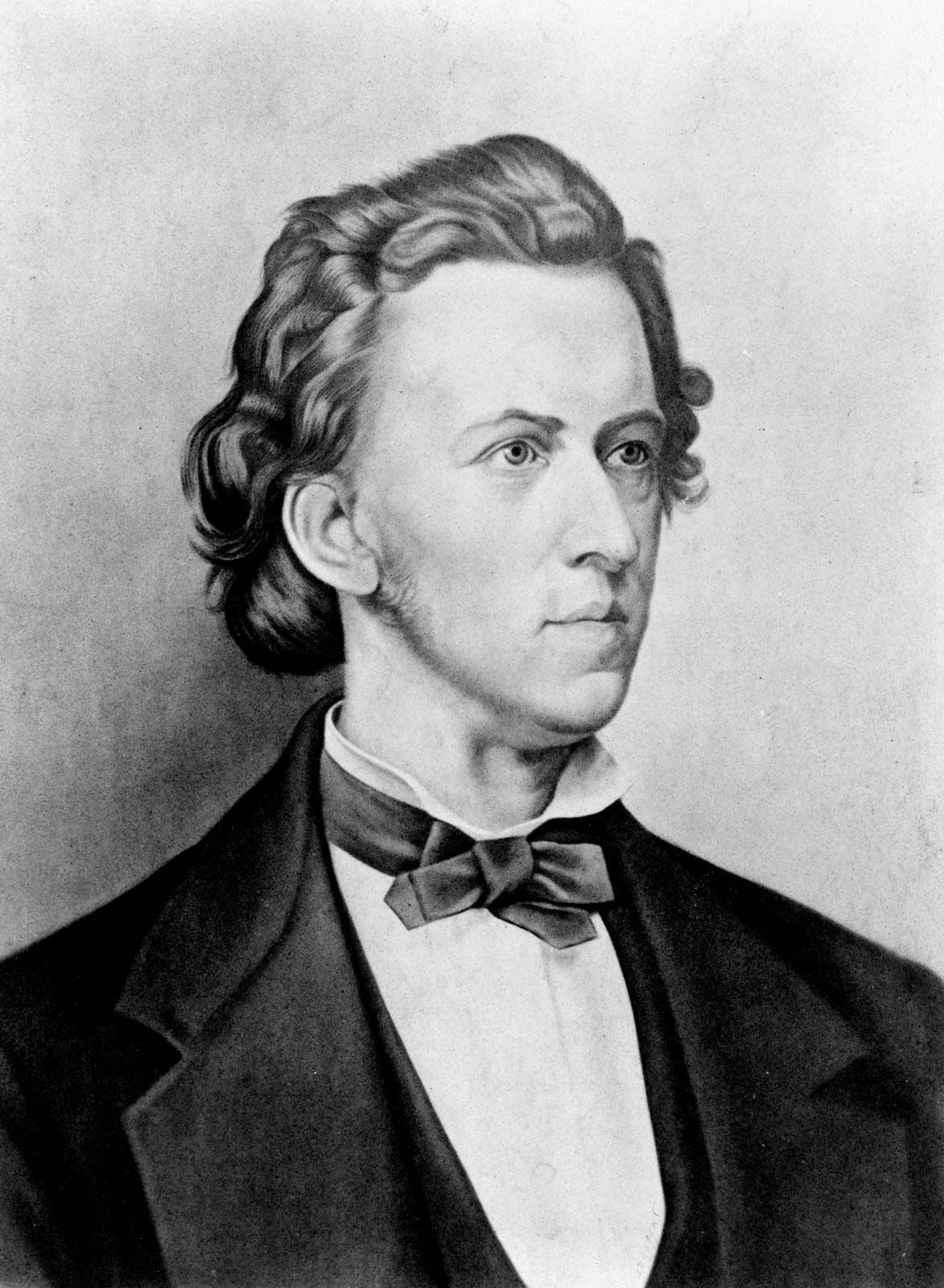

In his music, Chopin interwove love and longing for his homeland – he left Poland in 1830 at the age of twenty and never saw it again – sometimes with sadness, sometimes with caprice, as one does when one is consumed by a deep, insidious pain. It was precisely this pain that for many years marred Chopin’s public image. He was sometimes regarded as a composer of sweet salon music for melancholic young ladies eligible for marriage, and at other times as a weak man tormented by typically feminine obsessions. His appearance didn’t help him in this regard: Frédéric was frail and weak, partly due to suffering tuberculosis since his childhood, which he probably contracted from his younger sister Emilia, who lost her life to the disease.

There is pure love in his music. He had the capacity to fall hopelessly in love with a girl whom he had only just met and suffer for months, as was the case with singer Konstancja Gładkowska, a classmate at the Warsaw Conservatory, who completely ignored him. The years of his childhood and youth in Poland always remained in Chopin’s soul as the only truly happy period of his life, which he spent playing with his sisters Ludwika, Izabella and Emilia. Together they staged bizarre theatre performances, which Frédéric wrote himself as well as performing in them. In fact, Chopin was self-taught and learned everything his own way. No one could teach him anything: his piano technique grew and developed with him as if it were part of his body. The music he was searching for was different: in his wandering life, he tried to reconstruct a lost world of family affection, first loves, the sounds of popular songs he had heard in the countryside, and the natural environment of his solitary walks.

Chopin was too innovative for his time and didn’t have many followers at first. After leaving Warsaw (taking with him a silver cup containing some soil from his native land), he went to Wrocław, then on to Prague and Dresden, and finally to Vienna. They did not understand his art in the Austrian capital, which was no wonder: these were the years of “muscular” pianists in tailcoats. The keyboards were dominated by people like Franz Liszt and Sigismund Thalberg, Stefan Heller and the Herz brothers, musicians with a powerful, thunderous sound. It seemed that there was no room for the gentle Chopin, who nonetheless always maintained: “Nothing is more odious than music without hidden meaning.” In 1831, he finally arrived in Paris, where he immediately found adoration. He lived in rue Tronchet.

Chopin died aged 39 on 17 October 1849 at two o’clock in the morning, after receiving the last rites. He jotted down a final wish on a scrap of paper: “When this cough suffocates me, I implore you, cut me open, so that I will not be buried alive.” He was laid to rest in the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris, but according to his own wish, his heart was taken to Warsaw by his sister Ludwika.