A Symphony Is Like a World That Contains Everything

The new subscription season is open, and if you’re at all familiar with the Slovenian Philharmonic, you will know that it can offer everything you may want, and sometimes even more. Among the various options to which you can treat yourself is the so-called SMS subscription, the Symphonic Masterpieces Series. In this series, you can count on a large symphony orchestra and a luxurious palette of sonic colours, playing powerful compositions creating a whirlwind of diverse emotional moods. After all, music is just that: an emotional experience. We will get our first taste of this experience on 28 and 29 September at the concert entitled For the Beginning under the baton of conductor Charles Dutoit.

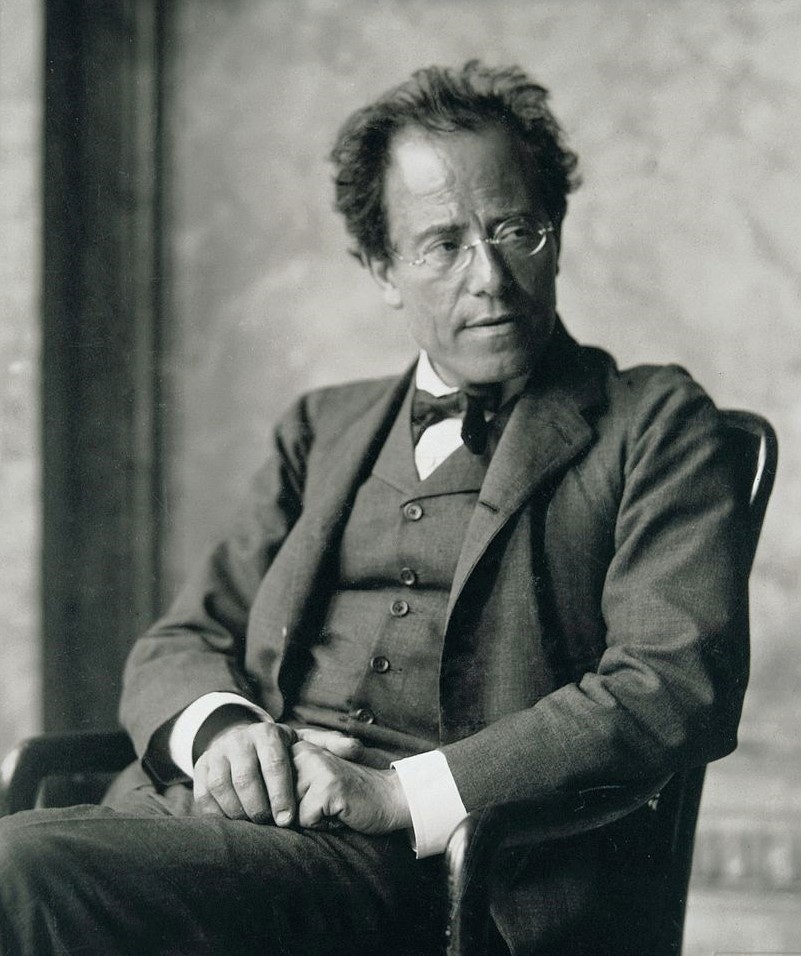

“A symphony must be like the world: it must contain everything,” proclaimed the unique Gustav Mahler. I didn’t know much about Mahler until recently, but I gladly did my homework and immersed myself in his world. At the end of September, we will have an opportunity to hear his Second Symphony in the Gallus Hall of Cankarjev Dom. It is a composition in which the orchestra is joined in the last movement by two female soloists and a large choir. This symphony represents one of the essential works of Romantic symphonic music, which, after the lofty heights reached by Beethoven, became the musician’s highest means of expression. Mahler completed nine symphonies and, like Beethoven, left the tenth unfinished, as he died while he was creating the work. His works are full of hidden meanings, as he believed that the symphony had to contain all forms of existence. Mahler was very thorough and didn’t want to conceal any element of reality. Thus, various worlds – of both high and folk culture – found a voice in his music.

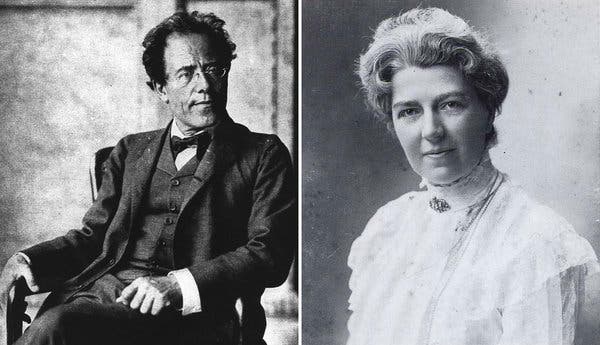

In July 1908, Mahler, who was one of the musical titans of the turn of the twentieth century, spent the summer in Dobbiaco, a beautiful town in Trentino, nestled in the Dolomites, where he composed the wonderful Das lied von der Erde (Song of the Earth), which is actually his Ninth Symphony. He composed it hidden in a quirky cottage perched at the edge of the forest together with his charming and restless wife, Alma Schindler, who was twenty years his junior, and whom he loved deeply. Mahler had a weak heart and undertook his creative work in the shadow of a premonition of death, obsessed with the fear that he would soon leave this world. Thus, in accordance with the historical period, his music became an inner analysis and a reflection of life in all its forms.

In 1910, Mahler met with Sigmund Freud after discovering that his wife was in love with the brilliant young architect Walter Gropius, one of the founders of the Bauhaus. The musician was deeply shaken by the incident and so was advised to consult a psychiatrist. Biographers report a single but lengthy conversation between the two men, lasting three or four hours. During the meeting, which took place over the course of a long walk, Freud learned that Mahler sometimes called his wife by his mother’s name, Marie, leading him to hypothesise that the composer was affected by the so-called “Virgin Mary complex”.

Recalling this episode, Freud later explained: “I had plenty of opportunity to admire the capability for psychological understanding of this man of genius. No light fell at the time on the symptomatic façade of his obsessional neurosis. It was as if you would dig a single shaft through a mysterious building.” One year after the meeting with the psychiatrist, Mahler died at the age of just 51.