Philharmonic Society

On the territory of present day Slovenia, and particularly within the circle of intellectuals that formed around Baron Žiga Zois, the period of the Enlightenment gave a new impetus to literature and science, and musical life was not overlooked. During this period, the “Philharmonische Gesellschaft” (Philharmonic Society) was established in Ljubljana and very soon many respectable patricians, merchants, teachers, priests and others joined the society.

With the rapid growth of the Society its main task was to prepare statutes for its organisation, the first of which was printed in 1796.

Article 1 clearly states the essence and purpose of the Society: to ennoble the emotions with a selection of good musical compositions and to influence taste by performing these compositions well within the circle of the Society.

The statute divided members into “performers and listeners, but the two are not separated and together form a whole”.

The Society accepted as members anyone it maintained would assist in the realisation of its goals. For a new member to be admitted a two-thirds majority was needed.

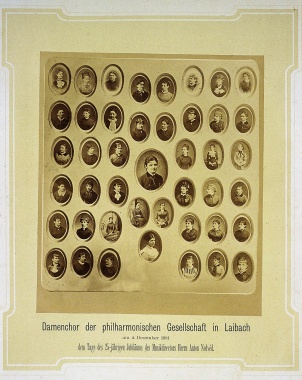

What about female members?

With regard to women, the statute stated that only female musicians who could contribute to the goals of the Society could be admitted as members. They were also allowed to bring a companion with them to an Academy. This article was later softened.

A member who left the Society due to the demands of professional work became an honorary member. “Foreign music lovers, who could benefit the Society with their brilliant musical talents and merit,” also became honorary members. The most notable honorary members were Josef Haydn (1800), Ludwig van Beethoven (1819), Nicoló Paganini (1824) and Johannes Brahms (1885).

The French wars of the 1790s did not spare Ljubljana and the unsettled times continued even after the wars ended. In the period from 1809 to 1813, the time of the Illyrian Provinces, it could be said that the Society maintained a “cultural silence”, remaining loyal to Austria and the Emperor.

At the beginning of 1809, the treasurer wrote with resignation: “French rule, a complete halt to the Society’s work.”

STANDING RULES:

“In order for the musical effect to be the best possible right from the start, it is necessary that following the first signal from the orchestra director the whole of the orchestra pauses and then after the second signal starts playing the music, in accordance with the instructions, attentively and strongly.” Article 5 states: “With compositions where more than one instrument plays the same notes, the basic rule is to play them as simply as possible. Each musician has to adhere strictly to the musical signs and must not hold a note for too long or too short a time, or play it differently; he must not place any stress or make any embellishments where there are none in the score; he must not play in too exaggerated a way at the beginning of the composition; and after ‘fermatas’ he must not play ahead but rather he should watch the orchestra director and continue playing in harmony with the others as much as possible. Non-compliance with this rule unpleasantly disturbs the unity and consistency of the production; the aesthetic whole appears as a multitude of tones overflowing, which makes listeners uncomfortable…”.

The Society helped to maintain its popularity with events such as the ever popular boat trips along the Ljubljanica River.

The season lasted for practically the whole year. It was divided into two parts: from 1 May to 31 October, and from 1 November to 30 April. Academies started at half past six in the evening. Sources also tell us about the composition of the orchestra. Data from 1802 states that the orchestra was made up of 25 musicians, comprising 4 first violins, 4 second violins, 2 violas, 2 violoncellos, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 flutes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, contra-bassoon, clarion and timpani – an orchestra that enabled the performance of almost the entire repertoire of the time.

The Philharmonic Society experienced another period of ascension in 1856, with the arrival of the Czech, Anton Nedvĕd, an excellent musician who was first appointed as the choirmaster of the male choir and later, in 1858, became the musical director of the Society.

“As a teacher, he smashed with a single blow the occasionally frightful remnants of empty music and led the Society back to its prior fame; only the best works, often classical, made it into the programmes. As a choirmaster, he did away with certain practices at concerts, practices that had managed to creep in and had a detrimental effect on the dignity of the concerts…”.

He attracted young musicians to the Society and included more demanding works in the concert programmes.

However, he had problems with the orchestra, as there was a lack of good musicians, which meant that musicians from the military orchestra often had to take part.

“Nedvĕd was dutiful, tireless and strong in the realisation of his obligations; an extremely knowledgeable and exceptionally talented man.”

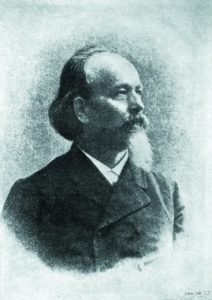

Another key figure in the history of the Society was Nedvĕd’s successor, Josef Zöhrer (1883–1912). Under Zöhrer, the Society made continuous progress and enhanced its reputation.

Appearances by well known foreign artists, some of whom appeared visited more than once, became even more frequent. Amongst them were violin virtuosi Pablo de Sarasate, Fran Ondřiček and Bronislav Huberman; the famous pianists Alfred Grünfeld, Emil Sauer, Eugen d’Albert, Leopold Godowsky, Paul Weingarten and Alfred Hoehn; singer, Leo Slezak; orchestras conducted by Richard Strauss, the Berlin Philharmonic with Hans Richter, the Münich Tonkünstler-Orchester with José Lassall, the Vienna Tonkünstler-Orchester with Oskar Nedbal, numerous string quartets (including the Bologna and the Rosé), to name just a few.

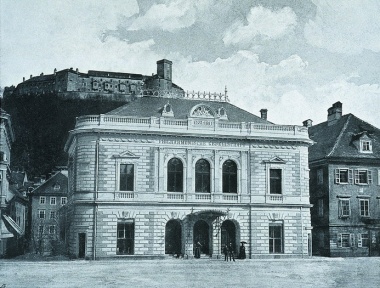

Another success was marked by the construction of a new concert theatre, with both a small and a large hall, on the site where the State Theatre had stood. The ceremonial opening was on 25 October 1891.

In the 1881/1882 season, when the young Gustav Mahler was employed at the Provincial Theatre, Nedvĕd invited him to play the piano at one of the Society’s concerts.